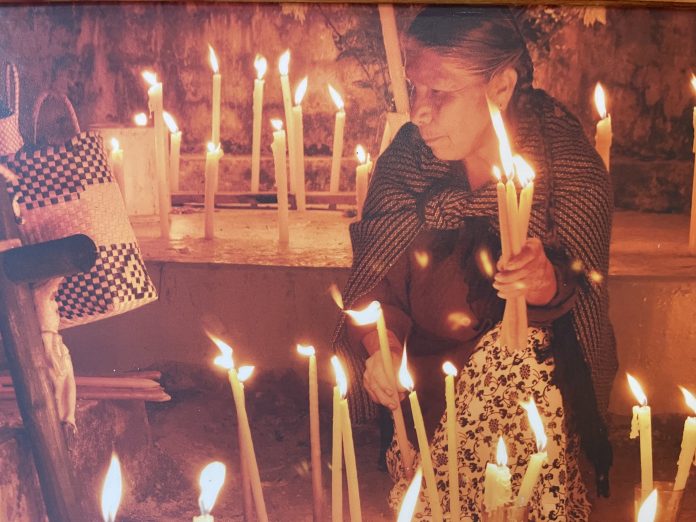

The mushrooms kick in hard in the middle of the night, lifting me out of my peaceful slumber and into a deep trance that I have no control over. It’s been five hours since I ingested the ‘niños santos’ during a private ‘velada’ ritual with the grandson of Maria Sabina in the homestead that her surviving family continues to maintain on an idyllic hilltop overlooking the Mazatec Pueblo of Huautla de Jimenez.

After two hours of laying on a dirt floor enveloped in copal incense and fighting off boredom, I’d decided that the mushrooms were impotent and surrendered to travelers fatigue.

I was incorrect in my assumption.

I’m catapulted out of a deep sleep and into a phantasia of open-eye visuals. ‘Open-eye’ is not a typo; one of my eyes was paralyzed shut, and I had zero control over either. I couldn’t blink even if I tried. I lay pinned to the ground, paralyzed by the total loss of control over my right eye muscles. While ‘awake’ in this condition, my left eye was paralyzed shut and unable to open. My ‘self’ was trapped between two different worlds; right eye was fixed to the ceiling of the dark concrete room, left eye frozen shut and attentive to a dream where I was blacked out drunk and getting detained in an airport.

Some part of ‘me’ is able to detach from both scenarios and appreciate that I’m experiencing a phenomenon that I didn’t know existed. I deliberate upon the distinct possibility that I am now permanently insane, and may spend the rest of my life in a catatonic state suspended between imaginary realities.

I appeal to the powers that be to go easy on me, and feel humbled by the forces that hold me in their grip.

I don’t know how long I’m suspended in the terrifyingly miraculous liminal state between worlds. It could be seconds, or hours.

In the dream, I break free of the airport authorities and dash into a nearby restroom. The floors are covered in excrement, and I slip and slide into the filth in my blacked out drunken state.

“I’ve had enough of this, please let me go” I offer to no one in particular.

The paralysis is released, and I’m left with a cascading flow of intricately detailed and technically stunning visions that don’t abate until the purple light of dawn breaks over the valleys below.

This was in July of 2010, and the first rains of the season broke forth during my three day stay with the Sabina family. It’s not commonly known that Sabina is not actually their name; it was an honorary title bestowed upon Maria Magdalena Garcia, the celebrated and controversial Mazatec curandera who first administered the sacred mushroom ritual to Gordon Wasson in 1955. This unassuming act of cross-cultural benevolence unintentionally opened the door to countless spiritual seekers over the next twenty years, with the influx of foreigners and hippies spiraling so far out of control that armed guards were eventually posted at the base of the mountain to keep non-natives out.

By the time I made the harrowing zig-zagging journey up the mountain, the legacy of Huatla de Jimenez had largely faded from global awareness. The name Maria Sabina was still widely recognized, but I didn’t see a single other foreigner during my time in the pueblo. This was an era before the resurgence of interest in psychedelics and the ‘psychedelic renaissance’ that has taken the world by storm; in fact, I was four years into my experiential studies in the fundamentals and dynamics of altered states of consciousness by this point, with few people to share my experiences and insights with.

My first out of body experience on a 14 gram macrodose of dried golden teacher mushrooms happened when I was 18, during the first semester of my undergrad at the University of San Francisco. I won’t bore you with the details of the trip, but it involved interstellar travel and deep immersion into ancient rites.

6 months before that, I had my first cathartic visionary experience on 7 grams of mushrooms. I had accepted that no one I knew in ‘polite society’ wanted to talk about or try to understand the high dose mystical states that I had grown accustomed to navigating.

10 years after my first experience at the Sabina homestead, mushrooms randomly started to become popular in mainstream western society. I watched, comically detached, as wave after wave of study into the efficacy of psilocybin mushrooms for treatment of various medical conditions were undertaken in laboratory settings and university research centers.

I wonder how many of the researchers mapping out the underlying brain functions of psilocybin-engendered states have ever taken 14 grams of their subject matter in a dark room, or experienced the relentless trance state bestowed by a jar full of mushroom honey blessed with copal smoke in a ramshackle concrete dwelling with no WiFi or cell phone service.

I returned to Huautla de Jimenez in February of 2022, buzzing with the excitement of being alive in an era when the magic of mushrooms was finally starting to be taken seriously by the people in my country of origin. In a time when billions of dollars are circulating around the ‘psychedelics industry’, with a huge amount of study and interest in psilocybin mushrooms, the Mazatec communities that maintained their ancient connection to these sacraments have largely been sidelined and ignored by the corporatization of psychedelic mushrooms; how many microdosing companies, synthetic psilocybin developers, coaches and retreat leaders and clinicians and conference organizers, etc.,are currently even aware of the treasure trove of data and documents consolidating hundreds of years of unbroken psilocybin mushroom research that lies collecting dust in the archives of Inti Garcia Flores?

Inti is the steward of thousands of hand-drawn maps, colonial era letters to the King of Spain, undeveloped photographs and 16 mm film rolls dating back to the 1930’s, undigitized audio and video recordings of Maria Sabina dating back to the 50’s, and countless other legacy documents related to the Mazatec culture of ceremony and reverence for nature. Above and beyond documents about psilocybin mushrooms, there is a stockpile of artifacts that map out the entire Mazatec cosmology and cultural practice – which includes ceremonies revolving around corn, copal, water, tobacco, and more. To single out the importance of psilocybin mushrooms is to excoriate the true value of their role in Mazatec society, and ergot, in mainstream society at large; the real magic of psilocybin mushrooms is found in their connection to the web of life that they help to sustain. To decontextualize mushrooms, or ayahuasca pills, or anything related to ‘psychedelic healing’ from the cultural frameworks in which they’re embedded is to devalue a significant component of their ability to heal people.

On my second stay with the Garcia (“Sabina”) family, I again had a chance to experience a private Velada administered by a direct descendent of Maria Sabina. While I didn’t experience the profound state of paralysis that overtook me on my first visit, I was bombarded with a deluge of hilarious plot lines for satire pieces – it seems that the mushrooms find satire and comedy as delightful as I do, and this certainty brought great joy and validation.

While I’m not suggesting that there’s only ‘one way to peel a banana’ , the hubris of so many people in the ‘psychedelic renaissance’ is difficult to ignore; I see people flooding in to position themselves as authorities on a subject that they only recently found out about, and find infinite comedic value in watching the armchair authority social media generation rush to establish dominance over this ancient subject matter that just popped up on their radars.

It reminds me of how the pandemic turned everyone into a virologist overnight – and then when Russia invaded Ukraine, suddenly everyone became a geopolitical strategist.

I’m in a position of influence and recognition in the psychedelic space not because I’ve pivoted from another area of research or enterprise to pull up a chair at the ‘psychedelic renaissance’ ; I saw the full value of these molecules and natural technologies years before anyone in my community was talking about them, and I made major sacrifices in my life and withstood over a decade of marginalization and belittlement by the same types of people who are now carnival barking about the value of microdosing and building sleek brands around the new personality they’ve adopted to fit into the psychedelic conversation.

I can only imagine how the Mazatec community feels being largely shut out of the ‘psychedelics industry’.